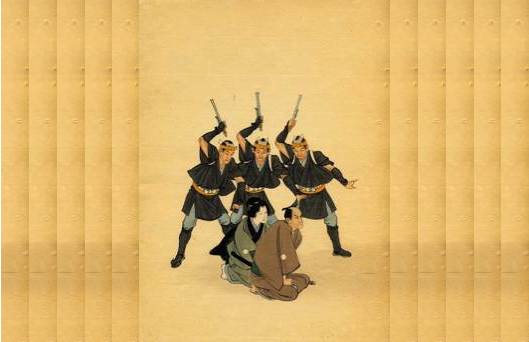

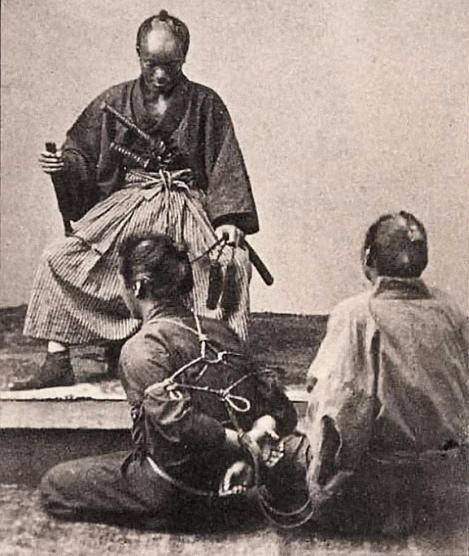

During Japan’s feudal Edo Period (1603-1868), low-ranking samurai policemen called “doshin” were charged with the hazardous duties of patrolling the streets of cities and towns, investigating crimes, making arrests, and generally maintaining the peace and civil order. In the course of performing these duties, doshin often had to arrest and/or defend themselves against various sorts of criminals who, given the severe nature of feudal punishment, were willing to sell their freedom as dearly as any samurai would sell his life. It was also often necessary to arrest well-trained samurai and/or ronin (masterless samurai), and despite the obvious hazards associated with such an undertaking, there existed a more subtle danger to the doshin as well, in that this frequently meant having to subdue individuals of higher social rank.

Performing such a task in the extremely caste-conscious culture of feudal Japan could be disastrous for a doshin if he failed in his duty, or inadvertently injured or killed the individual in the process. The resulting loss of honor could cost not only him, but his family as well, for the doshin profession was typically passed down father-to-son within particular families.

The Otaki family was one such line of hereditary doshin and took their family’s honor and survival seriously, recognizing that techniques to restrain and arrest individuals had to be effective, or else. To this end, they trained in various martial arts in and around the feudal domain in which they lived (the Otaki Han in Kazusa Province, modern-day Chiba Prefecture), and eventually developed their own family system of taihojutsu.

Incorporating both empty-hand (jujutsu) and weapons (buki) applications, this system—Otaki Han Taihojutsu—was honed over the years and passed down within their family and among close friends as a sort of “mongai fushutsu” (martial art managed within a given family as a “kaden” or family tradition). This continued throughout the Edo, Meiji, and Taisho Periods of Japanese history and into the early Showa Period when one Myoshi Otaki (1900-1976) inherited the system.

As a young man, Myoshi followed his family’s tradition of policing and entered the Japanese military, serving in the military police both before and during WWII. He brought with him to his post laudable skills in his hereditary taihojutsu system. However, during the course of his military career he was also privileged to receive training in Daito Ryu Aikijujutsu from its famous disseminator, Sokaku Takeda (1859-1943), who traveled extensively throughout Japan teaching that art in the decades preceding WWII. Approximately thirty thousand individuals are said to have been taught directly by Takeda Sensei—police and military personnel constituted the bulk of that number. Otaki Shihan later incorporated the Daito Ryu he learned into Otaki Han Taihojutsu.*

*The amount of training Otaki Shihan received in Daito Ryu is unknown, regrettably. Suffice it to say, however, that he considered its impact significant enough to stress it as a technical influence.

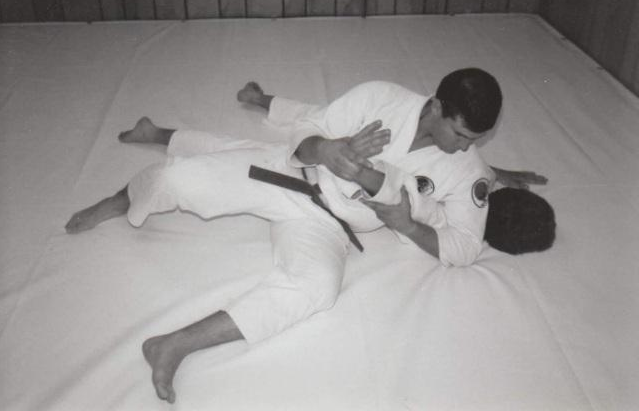

After WWII Otaki Shihan left Japan, going first to Brazil and then Canada before finally settling in South Pasadena, California, USA in the 1960s. It was in South Pasadena that a young Eric Merrill first met him. While practicing judo with a friend in a park one day, Eric noticed an old Japanese man sitting on a bench watching them. This man would later introduce himself as Myoshi Otaki, a retired WWII Japanese military policeman. As a result of this meeting, Eric and Otaki Shihan developed a relationship and eventually Otaki Shihan agreed to teach Eric his family’s taihojutsu system.

For the next decade Eric went to Otaki Shihan’s home daily to train (both before and after school) where Otaki Shihan would push aside the living-room furniture, throw down tatami mats, and teach. The training was severe to say the least (Otaki Shihan was an unpleasant, brutal man), but Eric persevered and his tenacity over the years was eventually rewarded when Otaki Shihan awarded him a Menkyo Kaiden (License of Full Transmission) in 1976. Shortly thereafter an aging Otaki Shihan returned to Japan to live with his daughter where he passed away following a stroke a few months later, leaving Eric as his one senior student and sole Menkyo Kaiden recipient, and thus the de facto inheritor of the system.

In 1977 Shihan Merrill decided to begin teaching the system and undertook the arduous task of organizing its heretofore largely uncategorized technical curriculum and structuring it for instruction to Westerners. At the time he was hesitant to use the Otaki name and instead taught the system as Goju Ryu Jiu Jitsu (and/or Goju Ryu Aikijujutsu). He taught the system under the Goju Ryu name until 2003 when he decided that the system’s name needed to be changed due to the fact that several American jujutsu systems also using the name Goju Ryu were discovered to exist. Given that Goju Ryu was a rather generic choice when he originally adopted it, it was not surprising that others had adopted it as well.

Ultimately, however, Shihan Merrill did not want these other unrelated Goju Ryu systems to be confused for—or assumed to be associated with—this system (or vice versa). Additionally, Shihan Merrill’s hesitancy in using the Otaki name had waned over the years and reasserting the system’s heritage and historical perspective seemed the proper thing to do.

To that end, simply returning to the system’s original name of Otaki Han Taihojutsu was considered. However, in order to avoid confusion at the time with modern taihojutsu (which differs from older, traditional feudal taihojutsu), the name Otaki* Han Doshin Ryu Jujutsu was chosen instead. By choosing this specific name Shihan Merrill was essentially returning the system to its original name of Otaki Han Taihojutsu, but with a slight play on words (Doshin Ryu translates to “Feudal Police Style”).

Over the decades that Shihan Merrill taught the Otaki Han system (under its various names), he re-envisioned how it could be used for more than just policing (i.e., as general self-defense and as a deep martial discipline worthy of lifelong study) and slowly refined and renovated it into its present-day form.

*For a number of years, the name “Otaki” was thought to be spelled “Otake” and the system operated under the Otake spelling during that timeframe. This was later discovered to be in error, at which time the original Otaki spelling was restored.

In 2005 Shihan Merrill closed his personal dojo and retired from public teaching, turning that responsibility over to his remaining senior students, Jon O’Neall, Phil Hillard, and Johnny Berghian. While Shihan Merrill no longer taught publicly, he did continue to privately instruct at quarterly yudansha classes and held yearly Tai Kai seminars open to all students of the system. During his retirement he continued to head the system administratively by way of the Otaki Han Doshin Kai (the organization created to serve as the administrative arm of the system).

Jon O’Neall, Phil Hillard, and Johnny Berghian were appointed to serve as members of the Otaki Han Doshin Kai initially and in 2011 were joined by Toby Scovel (another of Shihan Merrill’s senior students who had returned to the system after a brief hiatus). The Otaki Han Doshin Kai has since been repurposed and renamed the Otaki Han Komon Kai.

The system grew slowly but steadily over the next 14 years, adding students to its dojos and promoting several of them into the yudansha ranks. Shihan Merrill’s dream of creating a “clan” of students dedicated to the system and to each other via friendship and fraternity was being realized. Tragically though, on May 25th, 2019, Shihan Merrill was killed in an automobile accident (just weeks after retiring as the Deputy Chief of the Rio Verde, Arizona Fire Department—having served as a firefighter and paramedic for decades). This was a tragedy of enormous proportion for his personal family, his firefighter family, and his Otaki Han family.

In Shihan Merrill’s Living Trust, he designated Jon O’Neall as his chosen “successor” and thus the next Soden Shihan and head of the system. He also designated Phil Hillard, Johnny Berghian, and Toby Scovel to be Jon O’Neall’s “senior advisors”.

Additionally, Shihan Merrill stated in his Living Trust that after his passing he would like to be remembered as the “Soke” of the system. His reasoning was that the system as it is taught and practiced today is much more his and his senior students’ than that of Otaki Shihan (stating that Otaki Shihan was, “a brutal man… and I would like to start to separate our system from him except from a historical perspective”). Furthermore, with the Japanese lineage of Otaki Han Taihojutsu having died with Otaki Shihan, Shihan Merrill became its sole means of survival and over the ensuing decades its true revivor, renovator, and rightful inheritor. Thus, Shihan Merrill’s final wishes have been honored and he is now officially recognized as the Soke of the system.

In July of 2020, Jon O’Neall, Phil Hillard, Johnny Berghian, and Toby Scovel collectively decided to officially return the system to its original historical name of Otaki Han Taihojutsu. This was done to help better explain the system’s philosophical and technical approach to jujutsu and to reinforce its historical perspective and heritage.

Moreover, in modern times the term jujutsu has become so associated with Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ) and Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) that a distinction between those types of modern sport jujutsu and traditional Japanese feudal taihojutsu needed to be made for the sake of clarity. Prior concerns regarding any potential confusion with modern taihojutsu were therefore overridden by the need to differentiate the Otaki Han system from BJJ/MMA.